Any story of jazz in Colorado must begin with Charles Burrell, also known as the Jackie Robinson of classical music. Burrell, a bassist, is perhaps best known for becoming the first African American to ink a full-time contract with a major American symphony, as he did when he joined the Denver Symphony Orchestra in 1949. But equally impressive is his virtuosic career as a jazz musician, making him one of a rare breed who felt as comfortable in a tux at Boettcher Concert Hall as he did with a cigar in his mouth at Five Points’ Rossonian Lounge.The first notes of Tchaikovsky’s fourth symphony proved to be Burrell’s first exposure to an incurable music bug. As soon as he heard the San Francisco Symphony on his family’s crystal radio, the kid from Detroit made it his goal to play under the orchestra’s director, Pierre Moneteux. So, when his 7th grade music teacher asked if anyone wanted to play an instrument, Burrell eagerly followed him to a set of storage lockers and took the last thing left: an aluminum string bass so large his mother thrifted him a Little Red Wagon to help carry it.

To learn his instrument, Burrell practiced for hours every day. Some evenings he would get together with his friends and listen to the swinging sounds of Count Basie, getting his first feel for jazz and blues.Burrell aspired to become a music teacher but joined the Navy during World War II. Stationed at Great Lakes Naval Base in Chicago, he continued to hone his craft. He jammed in an all-Black big band with famous trumpeter Clark Terry and trombonist Al Grey, while also collaborating with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Northwestern University music groups.

When the war ended, he continued his music education at Detroit’s Wayne State University but was told he would never find work as a Black music teacher. Instead, Burrell hopped on a bus and moved west to Denver, where his mother had recently settled. A career in music wasn’t financially sustainable on its own, but Burrell paid the bills by painting and washing every one of the 9,000 seats at Red Rocks Amphitheatre — the very same venue where he would, hours later, don a tuxedo and perform with the symphony. Meanwhile, sporadic gigs at restaurants and nightclubs further sharpened his improvisational skills.

After ten years, Burrell left Denver and fulfilled his longtime dream, becoming the San Francisco Symphony’s first Black musician. He later joined the faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music as one of the institution’s first professors of color. When an earthquake shook the Bay Area in 1964, Burrell moved back to Denver, where he would play with the symphony until retiring in 1999. A staple of the local jazz scene, Burrell, who celebrated his 100th birthday in 2020, performed alongside the likes of Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole and Sarah Vaughan. Along the way, he mentored bassist Ray Brown (Fitzgerald’s husband), keyboardists George Duke and Purnell Steen, and his niece, singer Dianne Reeves, who herself is a Colorado Music Hall of Fame inductee.

Burrell has been honored with the Denver Mayor’s Award for Excellence in Arts and Culture and the Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award. Congresswoman Diana DeGette led a tribute to him on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, referring to him as “a titan of the classical and jazz bass.” But perhaps his most meaningful honor came on his 99th birthday, when the Colorado Symphony honored him with a rendition of the piece that started it all: Tchaikovsky’s fourth symphony. “I could not believe it,” Burrell told CPR in 2020. “I think it was the first time in my life I really shed a tear because it was so beautiful.”

Charles Burrell was inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame Jazz Masters & Beyond class of 2017

Charles Burrell Discography

Dreams Of The Skies

Sagebrush

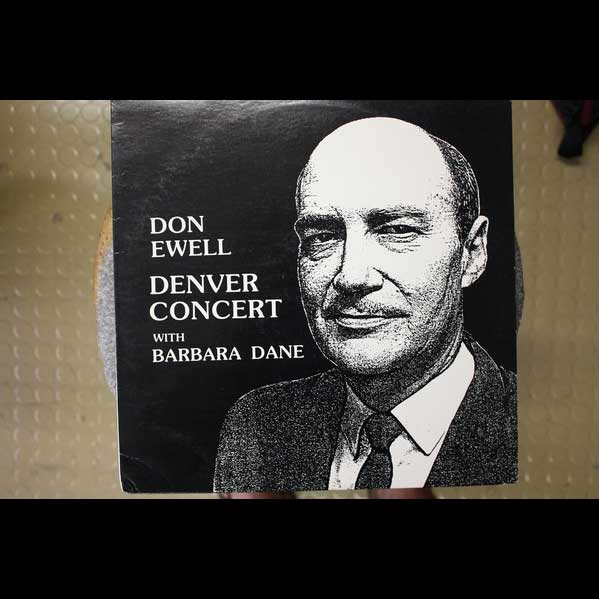

Denver Concert

Across The Blue Mountains