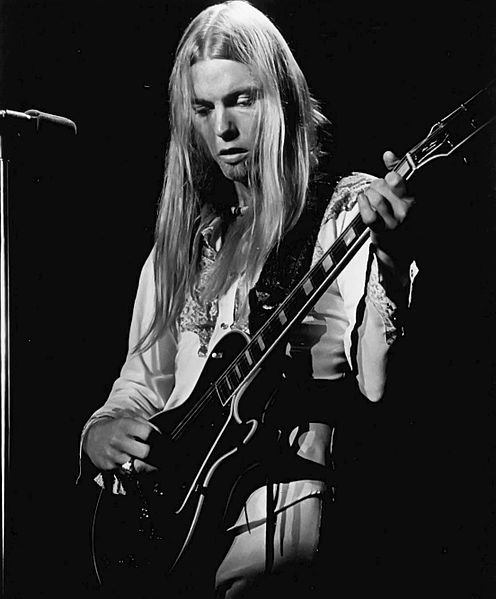

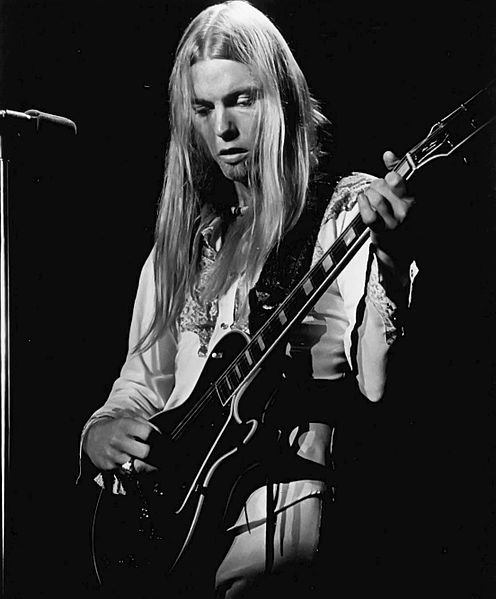

The death of Gregg Allman on May 27 at age 69 brought back memories of the countless Allman Brothers Band shows I attended over the years.

The death of Gregg Allman on May 27 at age 69 brought back memories of the countless Allman Brothers Band shows I attended over the years.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Allmans conjured a mix of virtually every American musical form – blues, country, R&B, jazz and rock – bound by an ethos of soaring concert improvisation. They disbanded, regrouped, splintered into various offshoots and disbanded again before coming back together in 1989 and garnering a new generation of fans.

Gregg Allman was the primary voice and face of the band, and I was lucky enough to spend time in his presence. The last time we spoke was when the 2003 edition of the jam-band progenitors performed at Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

Dickey Betts, who sang and penned many of the band’s trademark songs, had been forced out of the band on the eve of its 2000 summer tour, but the Allmans had found stability. An album called “Hittin’ the Note,” the group’s first release since Betts’ firing, was vintage ABB, and Allman’s world-weary singing had never been better. “High Cost of Low Living” was a cautionary tale of hard living, and Allman still sounded like the best white blues belter around.

“It sure sounds autobiographical,” Allman said. “If the shoe fits… it probably fits a lot of people.”

“Blues is usually about a good man feeling bad about a good woman,” he said. “Or not having any money, or a broken-down car. But the real art of blues is, you’ve got a story about a man that’s hurting, but somehow you inject some humor into it. Muddy Waters was a king of this, if you ask me.”

Allman claimed that Betts’ drinking and drug use interfered with the band’s performance. Cynics had asked if Allman was pot or kettle. He fought an alcohol problem for years and endured a much-publicized drug trial in the 1970s. But at 54, he seemed to have turned a corner.

“Butch (Trucks) and I were leaving (the band) – I had my letter already written out,” Allman said. “Somehow our wives got to talking. I didn’t know he was also leaving. So we got together and he asked me, ‘Are you through with it? Have you done everything you feel like you need to do in this band?’ I said, ‘Not really.’”

The Allmans rocked harder than a band with four AARP-eligible members were expected to. Laurels, they believed, weren’t for resting on.

“We try hard,” Allman said. “It’s weird how things happen and turn around. We landed on our feet.”

“It feels refreshing,” he added. “In the end, you get the same result, but more refined. I think it has to do with maturing. You’re putting a glaze on your art form.”

The last time I saw the Allman Brothers perform, I didn’t see Allman, literally. It was the 2006 pilgrimage to Red Rocks, a two-night package, the last shows of the band’s summer tour. Mother Nature made her statement on the first night. Large rain clouds surrounded the outdoor venue throughout the show, unleashing a long soaking. As temperatures plummeted to the low 40s, conditions started to affect the stage.

The road crew prepared a large steel box structure, then surrounded it with tarps on the sides and on the top, creating a “roof” for Allman and his keyboards. Large holes were cut on the sides so that the players and Allman could retain eye contact. The structure – guitarist Warren Haynes deemed it “the hut” – prevented some audience members from catching sight of Allman at all!

G. Brown

CMHOF executive director