Colorado Music Hall of Fame is grateful to have had several artifacts and newspaper clippings donated to our archives from El Chapultepec. The Hall of Fame will ensure its history is not forgotten.

Get your El Chapultepec t-shirt and other merchandise before they sell out – here.

Read more about the legendary club:

Westword: https://www.westword.com/music/covid-19-isnt-the-only-reason-el-chapultepec-is-closing-11858362

Denver Post: https://theknow.denverpost.com/2020/12/07/el-chapultepec-closing/250196/

5280: https://www.5280.com/2020/12/covid-19-isnt-the-only-reason-el-chapultepec-is-closed-permanently/

Denverite: https://denverite.com/2020/12/08/denvers-outgrown-us-el-chapultepecs-owners-and-friends-explain-the-demise-of-another-old-school-denver-landmark/

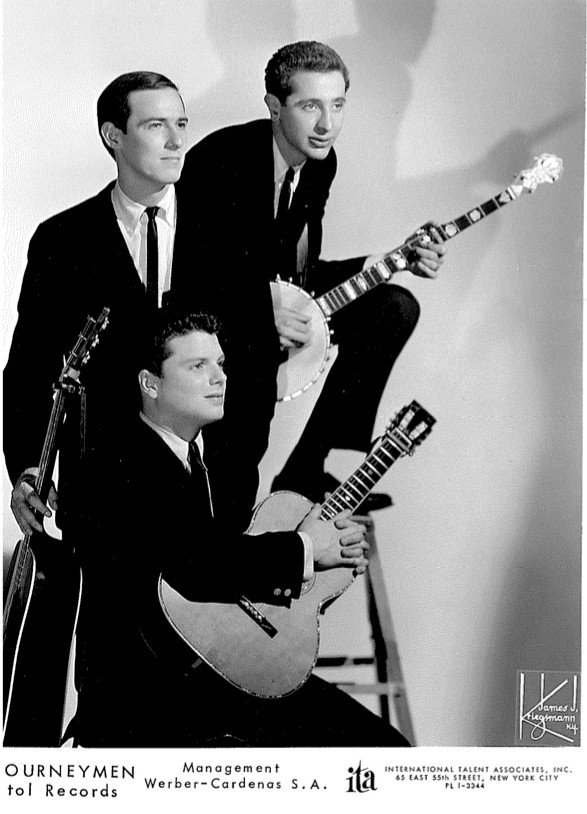

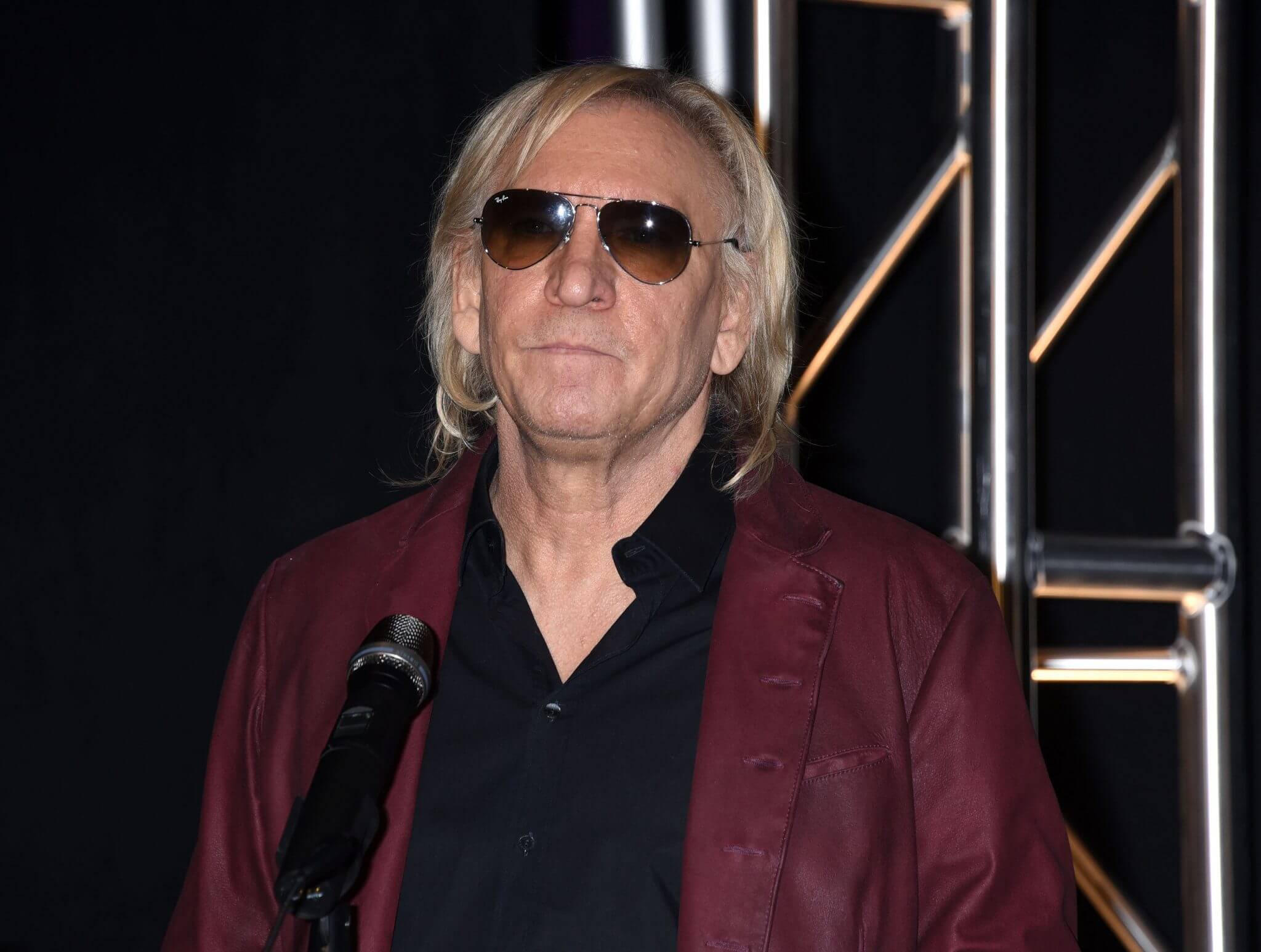

Photo Credit: El Chapultepec