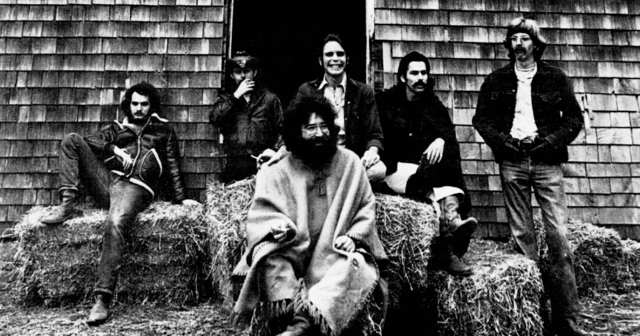

Deadheads know that the Grateful Dead, icons of rock, got their start in San Francisco, but the Dead also have a storied history in Colorado. The Grateful Dead’s Colorado legend began at a simple Denver venue in 1967; they would go on to play at all of Colorado’s most legendary venues and stadiums. Take a walk down memory lane with these facts about Rock and Roll Hall of Famers the Grateful Dead.

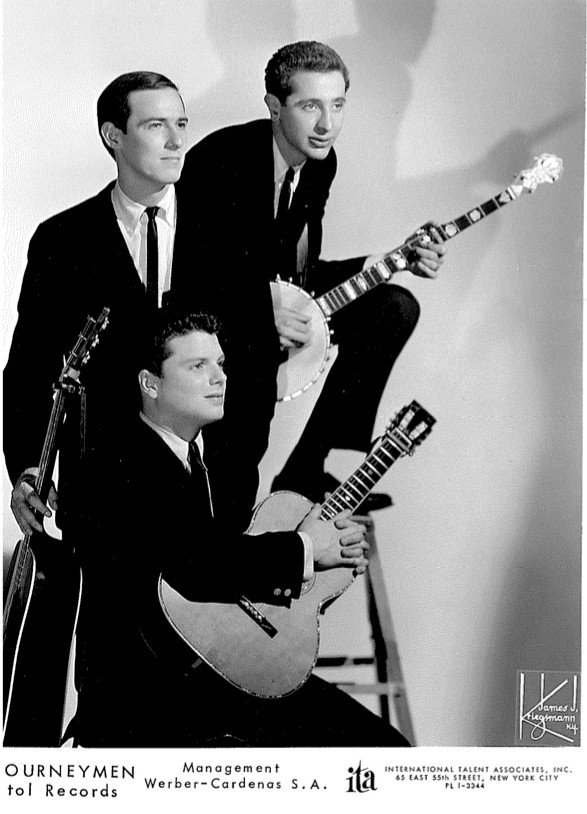

The Warlocks

Before they had settled on the iconic name we know today, the band originally went by the name The Warlocks. The only catch? Lou Reed’s The Velvet Underground put out an album of the same name, so Jerry Garcia and the gang decided they needed something more unique. While flipping through a book of folklore, Garcia happened across the phrase “grateful dead.”

The term appeared in folktales from a variety of cultures, and means a soul that is grateful to a charitable person on earth who arranges the soul’s burial.

The Dead on the Road

All said and done, the Dead played a staggering 2,317 shows from their beginnings in 1967 until Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995. While they put out an impressive 13 studio albums, the band was mostly known for their mellow, community-driven shows. Diehard fans of the band were known as Deadheads, and many Deadheads would follow the band around, going to all of their shows. Some fans did this for years.

Grateful Dead Colorado

Even though the band is best known for the members’ affiliation with the Haight-Ashbury district in San Francisco, the Grateful Dead history in Colorado is also impressive. In September 1967, the Dead played two shows at The Family Dog in Denver. They followed this up with their only acoustic set ever performed in the state n 1970.

They played Folsom Field for the first time in 1972 and then went on to regularly perform at Red Rocks Amphitheatre. The band later said that Red Rocks was a sacred space for their music.

Honoring the Dead

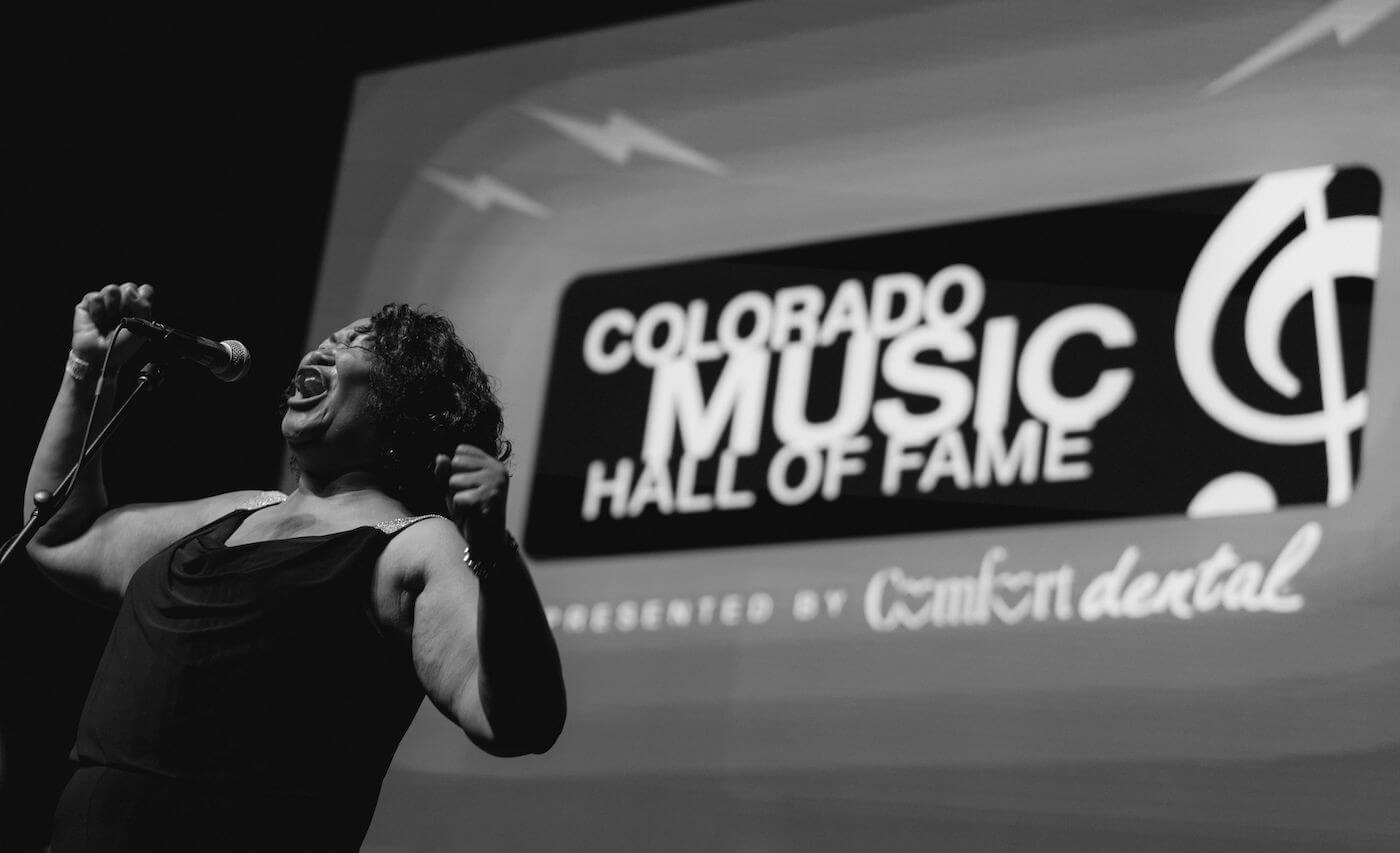

Despite their status as legends, the Grateful Dead never won a Grammy until 2007, when they were bestowed with a Grammy for Lifetime Achievement. The band was also inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994. They were further honored with an exhibit at the Colorado Music Hall of Fame titled “Colorado Getaway – The History of the Grateful Dead in the High Country.”

Their only chart-topping hit was “Touch of Grey.” This song reached number nine on the Billboard 100 in 1987.

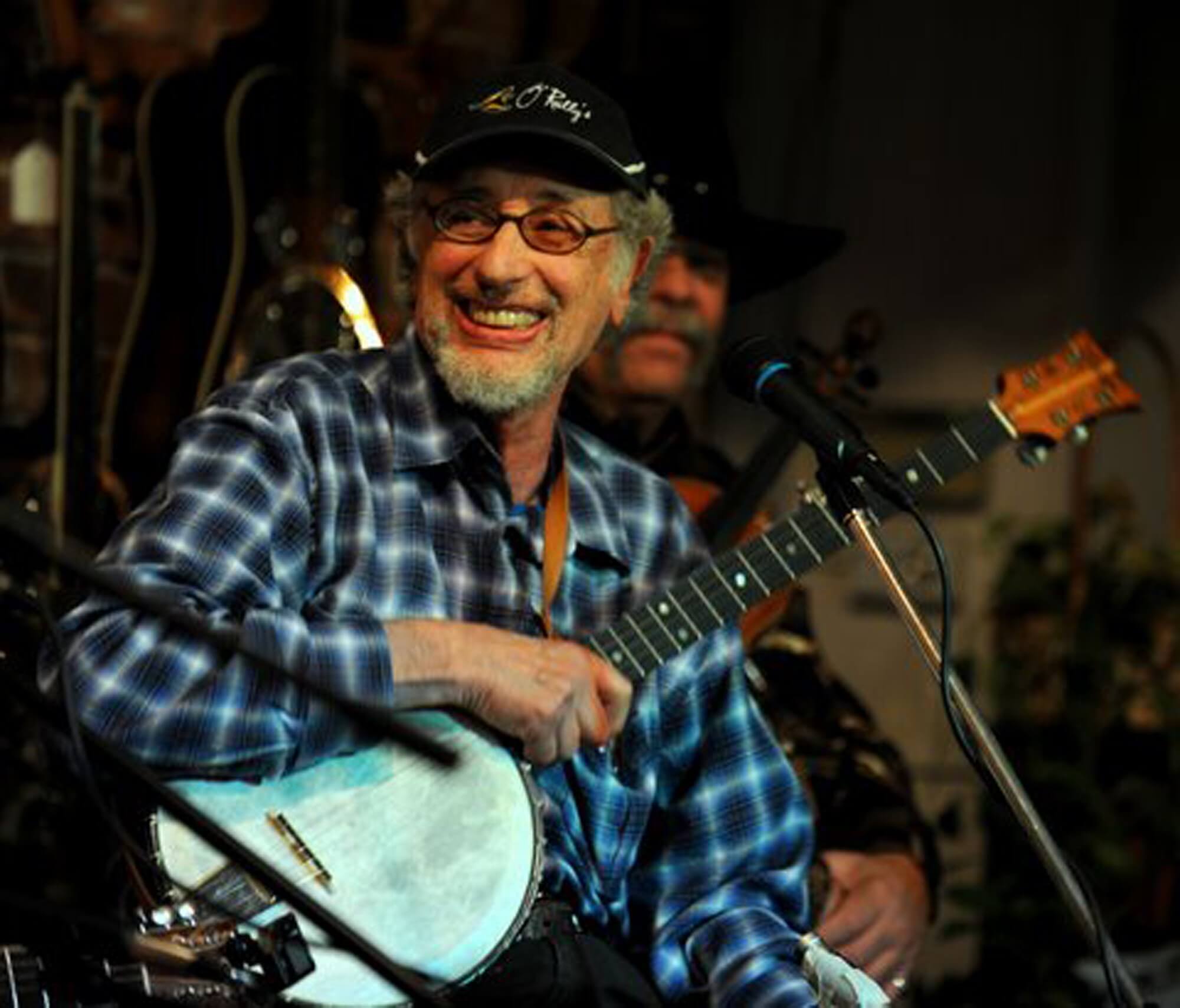

Jerry Garcia and Life After Death

Singer and guitarist Jerry Garcia was the heart of the band. He was an artist and songwriter responsible for many of the band’s greatest hits and artwork. Tragically, Garcia died of a heart attack soon after his 53rd birthday in 1995. The surviving band members continued to tour and play together; however, they retired the name Grateful Dead and went by names such as The Dead and The Other Ones.

Iconography

The Dead were known as much for their iconography as they were for their music. Fan art and T-shirts have been adorned with the band’s skull and lightning logo, dancing bears, and skulls and roses.

Legacy

Beyond creating beloved music, the Grateful Dead have done extensive philanthropic work through their nonprofit Rex Foundation. Since its founding in 1983, the foundation has raised more than $10 million for human rights, arts and education.

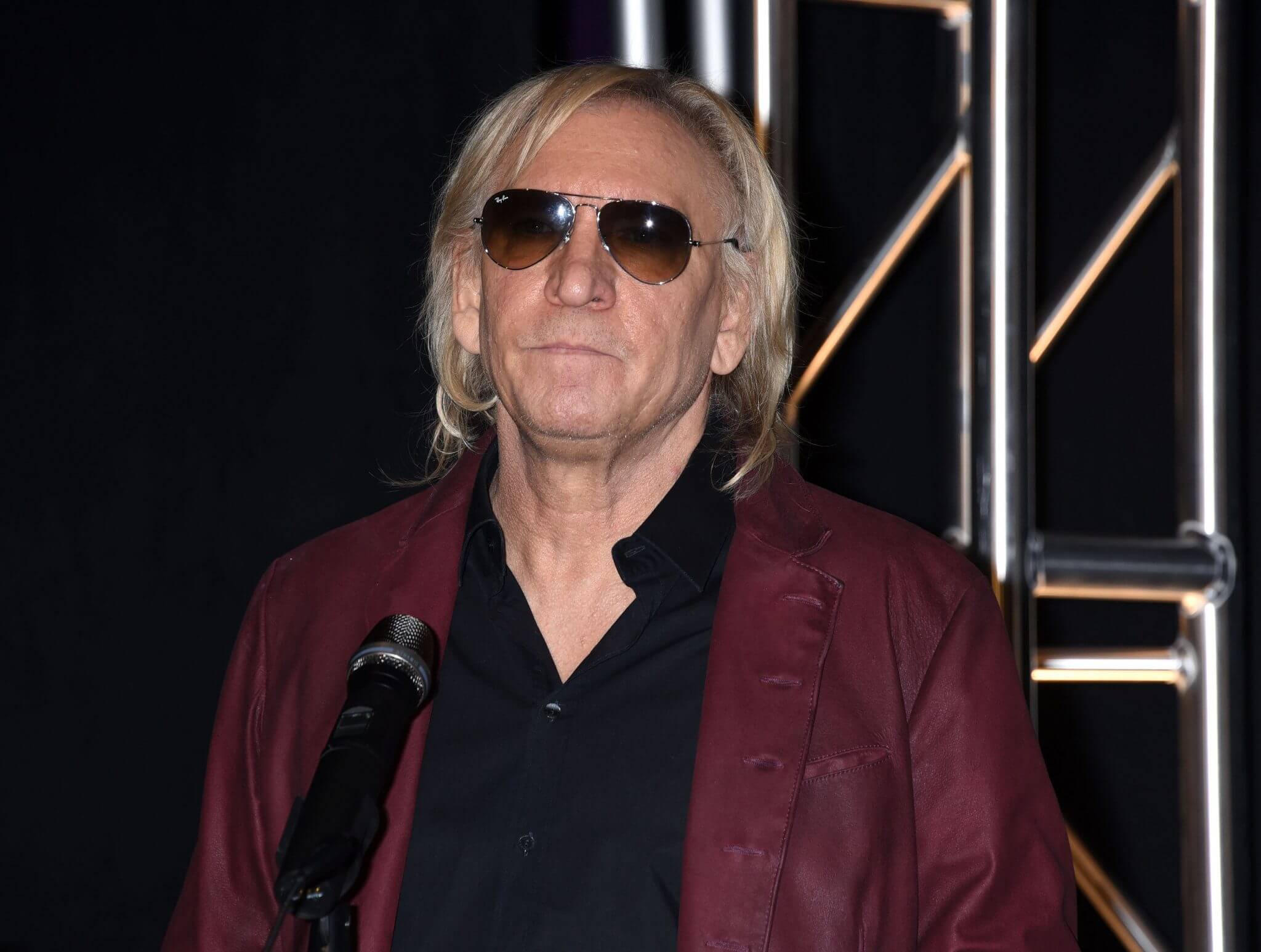

See Dead and Company at Folsom Field

In keeping with their love affair with the fans of Colorado, Dead and Company will be closing out their 2019 tour at Folsom Field. The band features original members Bob Weir, Mickey Hart, Bill Kreutzmann, and John Mayer who will fill in for Jerry Garcia. See the band and check out the Dead’s Colorado Music Hall of Fame exhibit “Colorado Getaway – The History of the Grateful Dead in High Country.”

This piece has been revised since it’s original posting in August 2017