DENVER, CO (February 26, 2021) – Colorado Music Hall of Fame (CMHOF) will celebrate its tenth anniversary with events throughout 2021. “Colorado Music Hall of Fame is ten years into an exciting journey of honoring and enjoying the music that makes our state unique….The most abiding takeaway for me has been the genuinely emotional connection that lives on between an artist’s output and the hearts and imaginations of the fans who experience that music,” says CMHOF board co-chair Paul Epstein, a founding board member and the owner of Twist & Shout Records.

CMHOF 10th Anniversary activities include:

March 24: In celebration of Women’s History Month, Patty Calhoun, founder/editor of Westword, will interview Lannie Garrett, 2013 Hall of Fame inductee, in a free, live Zoom that will include a Q&A session with the audience. Information on registration will be posted on cmhof.org.

April 22: On Earth Day 2021, eTown will be inducted into the Hall of Fame during a virtual concert celebrating eTown’s own 30th b’ Earthday Celebration. “We’re honored that eTown is being inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame. We’ve been working hard for thirty years to bring great music to our audience and have featured so many Colorado musicians along the way,” says eTown founder and host Nick Forster. Additional event details, including the lineup of performers and how to watch the live stream, will be announced in March.

May: This spring, CMHOF will host a 10th Anniversary online auction offering one-of-a-kind music experiences with some of Colorado’s most famed musicians and music industry legends. Visit www.cmhof.org in April for more information. Later this year, new Hall of Fame induction class exhibits will be installed at the CMHOF museum located at the Trading Post at Red Rocks Amphitheatre. At the start of the year, the Hall of Fame launched an online shop featuring CMHOF-published coffee table books and other music-related merchandise. Proceeds from purchases support CMHOF’s mission, to start shopping, click here!

About Colorado Music Hall of Fame

Founded in 2011, Colorado Music Hall of Fame is a nonprofit organization with the mission of celebrating our state’s music heritage and inspiring the future of Colorado music through our museum, educational programming, induction concerts, and events. Since the inaugural induction of John Denver and Red Rocks Amphitheatre on April 21, 2011, CMHOF has hosted eleven inductions, honoring more than forty musicians, individuals, and institutions who have made a mark on Colorado’s music history. Sharing the legacies of Colorado music, inductee biographies, videos and memorabilia are exhibited at the Hall of Fame’s museum, located at the Trading Post at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Morrison, Colorado. In 2021, CMHOF welcomed three new board members: Carlos Lando, General Manager of KUVO; Troy Duran, CFO/COO of Growth Leasing LLC; and Yvette Pita Frampton, community leader/documentary filmmaker/musician. It also launched its inaugural Board Emeritus with former board members JC Ancell, Aaron Friedman, Phil Lobel, and David McReynolds.

About eTown

eTown, the internationally syndicated radio broadcast, podcast, and multimedia/events production nonprofit, was launched on Earth Day 1991 in Boulder, Colorado. Since then, eTown has produced musical, social, and environmental programming all focused on its ongoing global mission—to educate, entertain, and inspire a diverse audience through music and conversation in order to create a socially responsible and environmentally sustainable world. Prior to the pandemic, eTown recorded shows in front of a live audience in eTown Hall, a 17,000 square foot former church in downtown Boulder which has been renovated and transformed into a solar-powered performance and recording facility—likely the only zero-carbon facility of its kind in North America. Recently, eTown pivoted to all-virtual episodes. eTown has aired on over 300 radio stations nationwide, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Podbean, Vimeo, on Facebook and Twitter @eTownRadio, on Instagram @eTown_Radio, on YouTube, as well as at www.etown.org.

Colorado Music Hall of Fame Induction Classes 2011-2021

2011- Inaugural Class: John Denver, Red Rocks Amphitheatre

2012- Setting the Stage: Barry Fey, Harry Tuft

2012- Rockin’ the ‘60s: The Astronauts, Flash Cadillac, KIMN Radio, Sugarloaf 2013- Colorado’s Folk Revival: Judy Collins, Chris Daniels, Bob Lind, Serendipity Singers

2015 – Country Rock in the Rockies: Firefall, Manassas w/Stephen Stills, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Poco

2016 – 20th Century Pioneers: Lannie Garrett, Glenn Miller, Max Morath, Billy Murray, Elizabeth Spencer, Paul Whiteman

2017 – Rocky Mountain Way: Caribou Ranch, Dan Fogelberg, Bill Szymczyk, Joe Walsh & Barnstorm

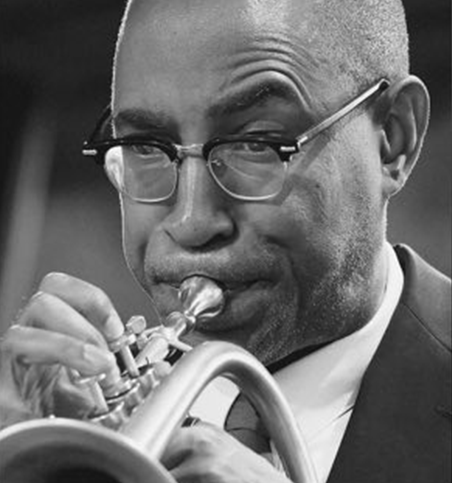

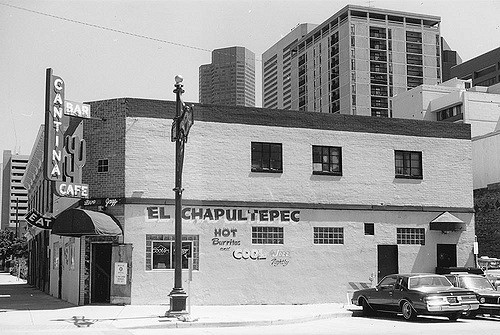

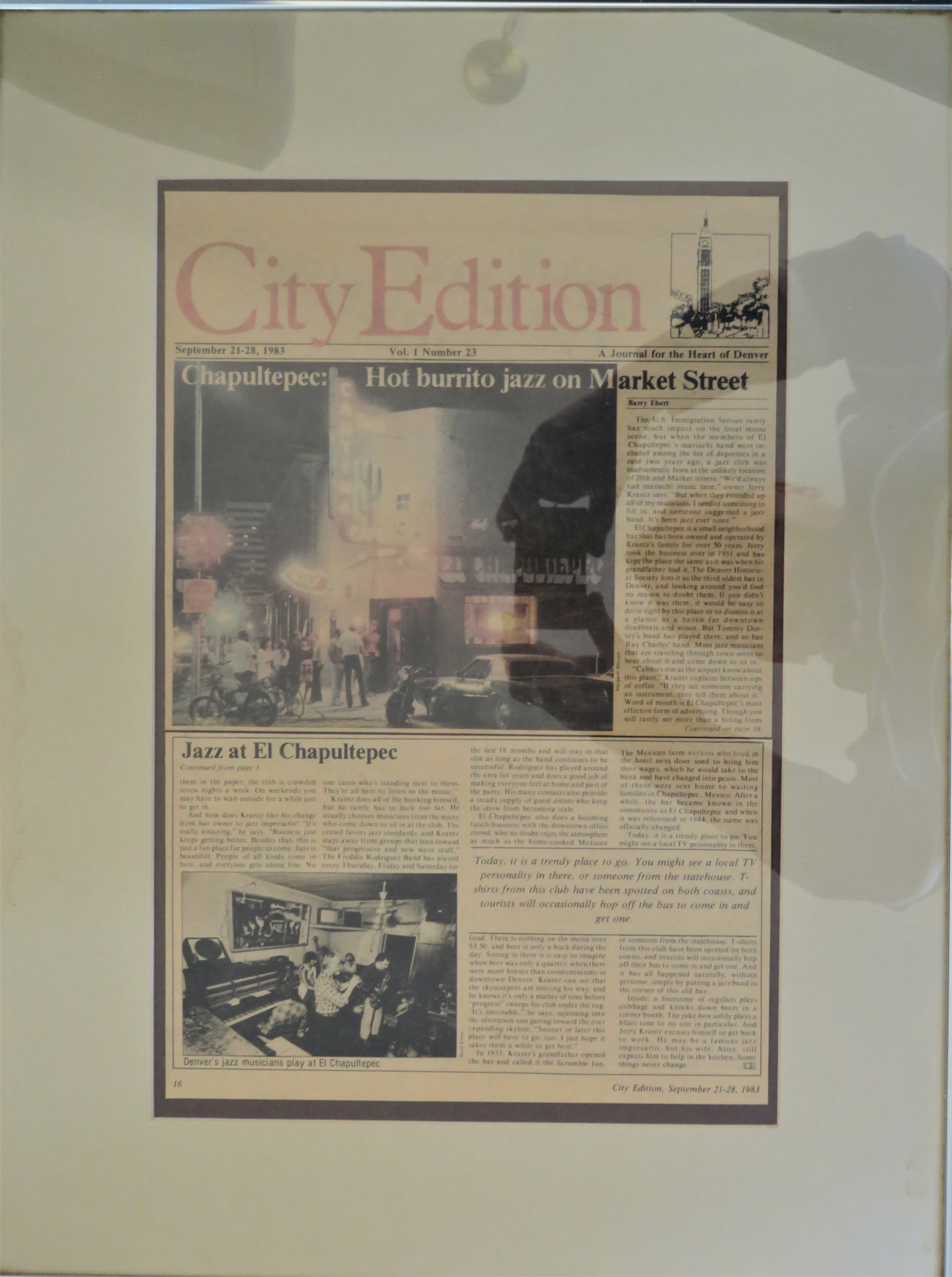

2017 – Jazz Masters & Beyond: Philip Bailey, Charles Burrell, Larry Dunn, Bill Frisell, Ron Miles, Dianne Reeves, Andrew Woolfolk

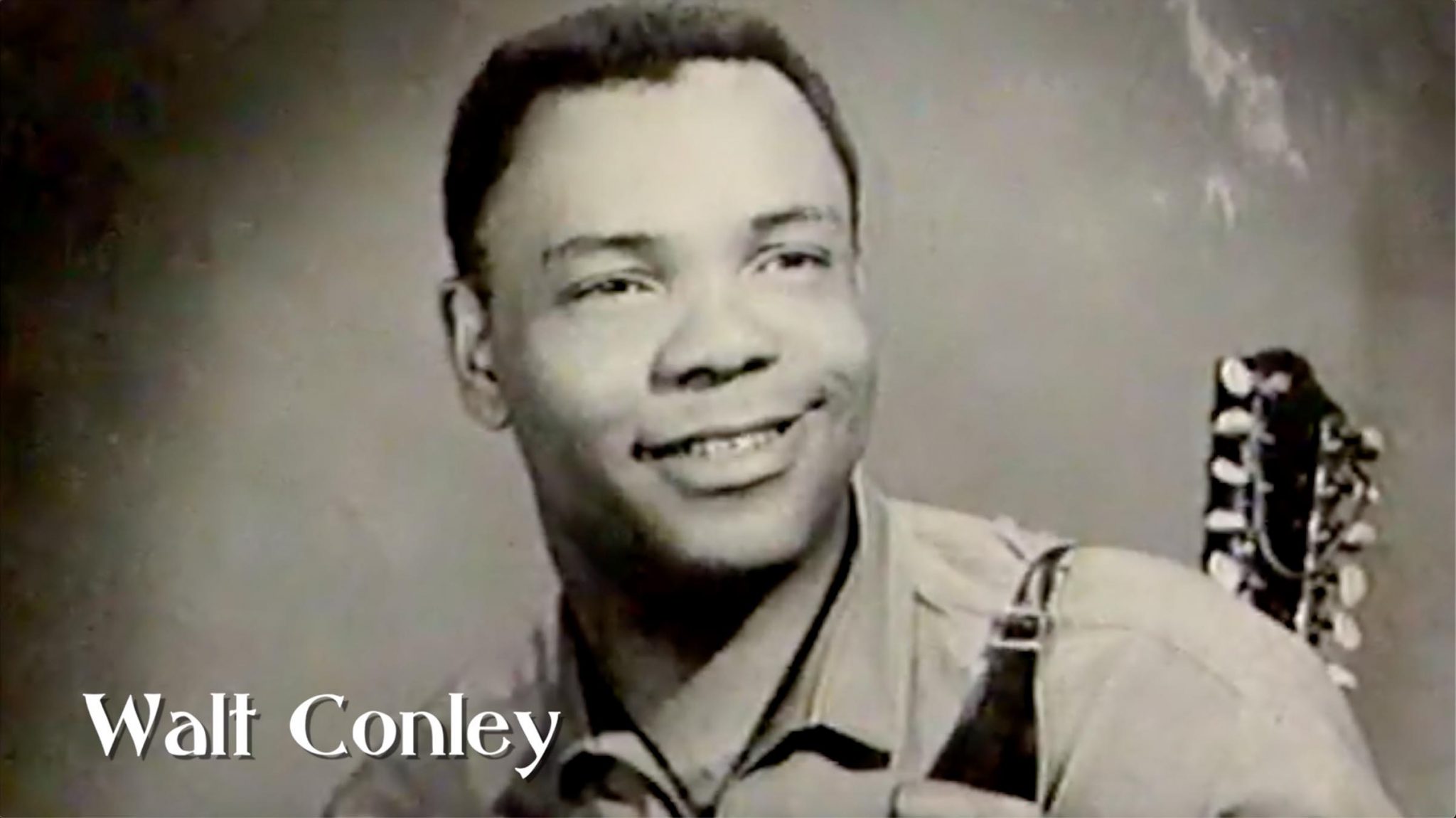

2018 – Live & On the Air: John Hickenlooper, KBCO, Chuck Morris 2019 – Old Folk, New Folk: Walt Conley, Mother Folkers, Swallow Hill Music, Dick Weissman

2019 – Going Back to Colorado: Tommy Bolin, Freddi & Henchi, Wendy Kale, Tony Spicola, Otis Taylor, Zephyr

2021 – eTown