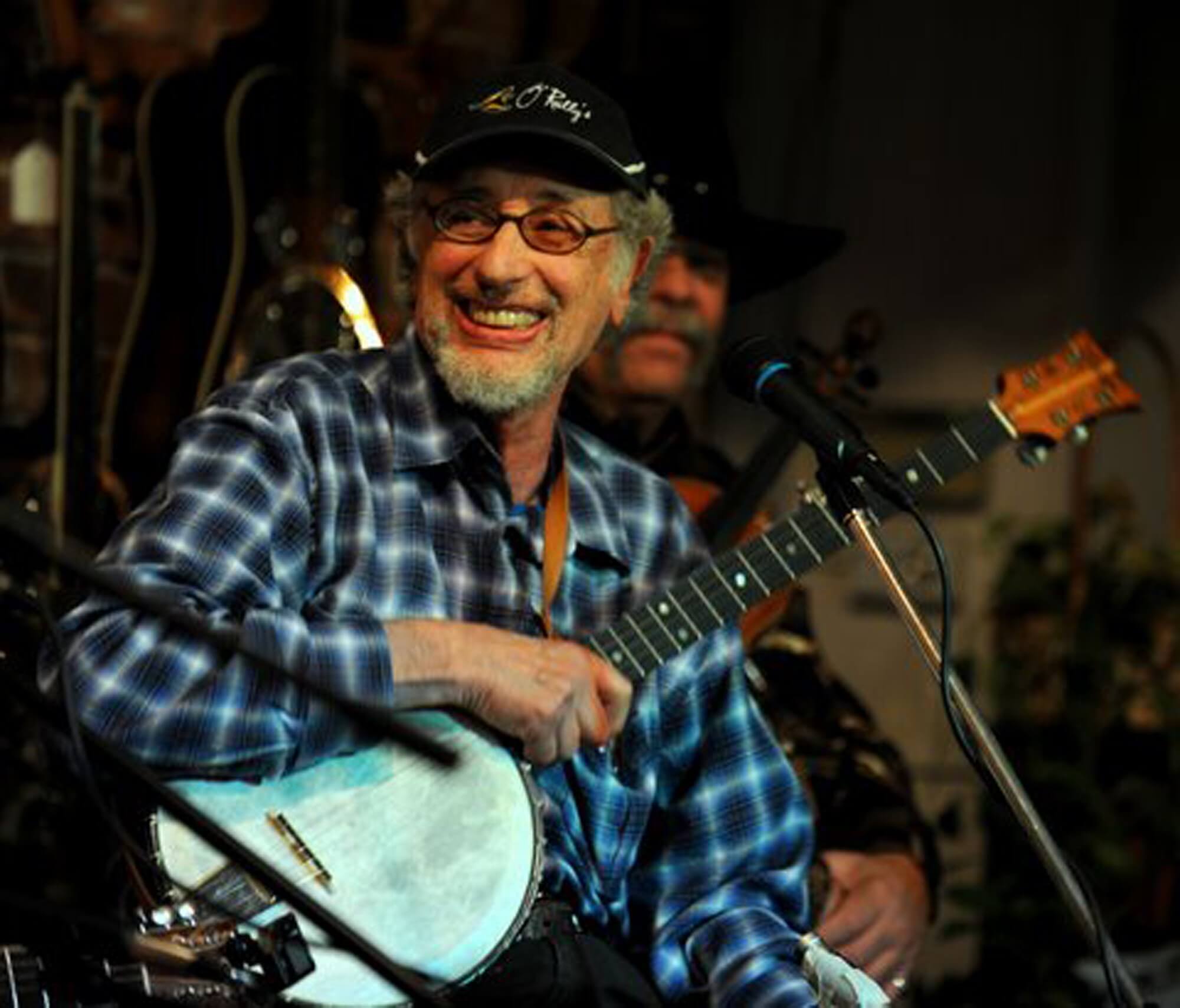

Dick Weissman is an entirely unique mix of historian, musician, teacher, and mensch. He has his curmudgeonly side, but his genuine love of music and understanding of the times in which he lives permeate everything he says.

His self-effacing manner belies a sharp and incisive wit, whether he’s dispensing wisdom to a class full of music-industry hopefuls or picking his way through a complicated banjo piece before a rapt audience.

Weissman is never less than completely honest and authentic. As he speaks his mind, his manner recalls a different America and a different type of American: the type for whom art is an occupation, not an abstract concept, and to whom civic engagement is an obligation, not an antiquated joke.

He is part of a tradition of American folk musicians who helped define the national character at crucial times in our history. He should be heard and cherished, and he is right here in Colorado.

We spoke on St. Patrick’s Day 2019. As his thoughts unwound in lengthy reminiscences, it felt like the history of modern culture was coming alive. Weissman’s experiences are defining, and trace the development of the now thriving music scene we enjoy in Colorado.

The Early Years

Q : Tell us about your early life and your first introduction to Colorado.

A: I grew up in Philadelphia….My parents had a commuter marriage: my mother was teaching public school in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn and my dad was a pharmacist in Philadelphia, had a little drugstore.

It was during the Depression, and my mother didn’t want to quit her job because she was afraid of what happens if this drugstore goes under? So my big hobby was collecting travel booklets.

I had all of these Western booklets. So I had a box full of this stuff and I was pestering my parents — my father took very few vacations, he was kind of an immigrant boy who worked 7 1/2 days a week – and when I was 13, we went to Colorado and New Mexico…

…Driving.

This would have been in 1948. That’s where I met this sort of old railroad worker at the State Capitol who wanted to talk to me: He fascinated me but frightened my parents.

I talked to him for maybe ten minutes, but it was kind of a peak experience for me at that age because everybody I knew was pretty middle class, my parents palled around mostly with medical people. So that was my first interest in Colorado.

I then went to college in Vermont, which is where I first learned how to play the banjo from a person whose name was Lil’ Blos, whose main claim to fame was her father, Peter Blos, who was one of the last living associates of Sigmund Freud.

I had heard Pete Seeger at the age of 13, at the Progressive Party convention, because my brother was very active in unions and politics. So Seeger kind of intrigued me, and I started to buy all these old records, 78 discs.

One of the things about me that is different from most of the folkies is that I got equally country-ish and bluesy things. So I had Seeger and Woody, but I also had Brownie McGhee and Lonnie Johnson. When 78s were phased out, Walgreens would have five for a dollar and I would buy 78s by Big Bill Broonzy, Memphis Minnie and people like that.

Q: Based on what? How did you know to go by Big Bill Broonzy?

A: I started doing some reading and also I went to a few Seeger concerts, who was always pretty generous without doing the sort of scholarly schtick that the New Lost City Ramblers did: “I learned this from Blind Paul Epstein who learned this from Deaf Dick Weissman, who learned it from his dog.” Seeger didn’t do that.

He said, “If you like the way I play this, you really should really hear Pete Steele do this.” So I would try to find out who’s this Pete Steele, how do I find this out? Seeger was an evangelist that way; that was very constructive and non-egotistical because there’s nothing in this for him to turn people on to those folks.

My junior year (1954) at Goddard in Vermont and then The New School in New York City was probably my formative musical period, when I took guitar and banjo lessons from Jerry Silverman, who was one of the Hootenanny crowd.

In the fall I met The Reverend Gary Davis: I played banjo with him, but never took lessons. He was very influential in my understanding. He played at Tiny Ledbetter’s house on Thursday nights.

Tiny was Leadbelly’s niece, who lived in the same building that Leadbelly and Martha had lived in. In the spring I had gone to the University of New Mexico and met a guy named Stuart Jamieson.

He had collected banjo music from a guy named Rufus Crisp in Kentucky. Rounder later put out a CD called Black Altamont, and Stuart produced a lot of those recordings.

So I met these two people, and the way they influenced me was Gary created this atmosphere around himself where you were sort of lost in this world of 1920s black evangelicals — you know, you’re gonna go to hell if you don’t straighten out.

Yet there was a schizophrenic kind of thing where he loved to have pretty girls around him, and he’d ask them to hold his hand and do crap. He would sing blues when his wife wasn’t around. After a beer or two and a little coaxing, he would do ragtime stuff.

So he was one level of inspiration, and Stuart had this certainty about what he did…he may have these insecurities, but it’s not apparent. Seeger was not one of those people. I don’t think that what he did came naturally to him.

He had to work to do this, and I would, of course, say the same thing about myself. I didn’t grow up in an environment where blues and banjo music were being played on the predecessors of Dick Clark.

So it was partially through Seeger’s influence, partly through buying these records and the radio. I wasn’t a real happy adolescent, so anything different appealed to me.

Q: So it was cultural osmosis, sort of the natural alternative to the “grey-flannel 50s”?

A: Yeah, exactly. So, when I was a senior at Goddard, I wrote the first lengthy banjo thing that I had ever done.

Q: Which you learned to do…?

A: I made it up. I created a form that, as far as I know, no one else has used. It’s called A Day in the Kentucky Mountains, and there are three instrumental parts and a song.

The song does what instrumental music does in most non-classical music — so instead of a banjo break, there’s a song break.

I don’t know why I did this, and I’ve continued to do it. So I graduated, came to New York, started working on a degree in sociology and started to get calls for sessions.

There was a music store called Eddie Bell’s and all the session guys would hang out there, and none of them knew how to play 5-string banjo — they all played tenor banjo. I remember I did a session for Raymond Scott that was one of my first sessions.

Raymond Scott was this crazy person who wrote experimental music, but he also wrote jingles. On the session are Barry Galbraith and Al Caiola, who are two of the biggest studio guitar players in New York.

They were very curious about what the hell I was doing — they hadn’t really seen anyone playing the finger-style banjo, not bluegrass banjo but sort of like old-timey music.

I would start to get more of these sessions and I took all my credits at Columbia and I wanted to write a thesis on five blind black blues religious artists: Gary Davis, Blind Blake, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie McTell and one more.

I realized that writing this would be like warfare with my advisor. I had this theory that non-literate blind people — and I was ignorant to the fact that McTell was not non-literate, he actually knew how to read and write Braille, and could write music in Braille — who had been blind since birth or an early age were residues of the culture that existed at the time that they went blind.

I ended up writing an article, but that was about it. So that’s sort of where my Colorado thing started. I had hay fever in August for about three weeks, so I tried to get out of New York. The first time I went back to Colorado I was 23.

Dave Van Ronk was a friend of mine in New York; one of my weird sources of income was that I taught Van Ronk a song called “Bamboo,” and it was recorded by Peter, Paul and Mary on a record that sold multi-platinum and we split the copyright, which was a joke because it was a traditional Jamaican song, but that was the game that was being played in the mid-’50s until the mid-’60s.

Dave was in ASCAP and I was in BMI and you were not supposed to work together, so after the first pressing my name was taken off everything after the first pressing, but he continued to pay me my half.

Q: On an informal basis? “Hey, buddy, here’s some more money”?

A: Yeah, and years and years later, he made it into a shoe commercial in Germany and I got an additional ten grand over time. I still get money from it, because after Llewyn Davis (Inside Llewyn Davis), Folkways issued a Van Ronk box set and that song is on it.

Q: What did you think of Llewyn Davis?

A: I hated it! It presented folksingers as being just like pop singers. The story I just told you about Dave Van Ronk — that wasn’t part of Llewyn Davis.

We had personal friendships and relationships.

I’m not saying everybody was honorable, I’m not saying there wasn’t some level of competition, but none of that spirit is in Llewyn Davis. The other thing is that black people are totally invisible. There is no black person in Llewyn Davis.

So, Dave told me I could get a job at Hermosa Beach working at this club. I didn’t know anything about Los Angeles at this point; I didn’t have a car, I didn’t know how to drive. Hitchhiking back to New York, I get stopped in Colorado because it is illegal to hitchhike, and the state cops escort me to the bus station.

So I go to Al’s Loans on Larimer Street, and I bought three cheap guitars, go to the bus station and there’s Tom Paxton.

I don’t know what he’s doing in Denver, but we were both going to New York, so he and I played for about an hour until I realized that people were trying to sleep. He would have kept playing.

There was no stop sign in his vocabulary for that. So that was my first trip to Denver.

Denver in the Late ‘50s and ‘60s

Somewhere in there, I met Walt Conley, who was one of the three best-known folk people in the Denver area, with Harry Tuft and maybe Judy Collins.

A couple of years later, I had a friend who was a guitar student of mine named Art Benjamin, and I said, ‘Why don’t we drive out to Denver?’

The first thing I did was to look up Conley, who lived in a house somewhere between Capitol Hill and Five Points.

His house was a 24-hour-a-day party, and there were friends and girlfriends, whatever. This was ’59 and he was slightly older than I was. I only recently found out that Conley was working for the FBI, reporting on radical folk singers.

Because of the nature of Walt’s house, I met a woman named Karen Dalton, and she and I started a relationship, and my friend Art started a relationship with her sister, who was 17 years old and had been married for ten days to a folksinger named Dave Hamill.

Walt was booking the Satire Lounge and I ended up as the opening act: Walt would do a set, and then The Smothers Brothers would do a set. Dickie Smothers, who was the straight man, his wife was working as a waitress at The Satire — it was so early in their career that his wife had to work as a waitress in the club.

The Satire was a pretty wild and wooly place in those days. That was great fun for me. I can’t remember what I got paid –probably $10 or $15 a night, but I didn’t go out there to make money: I went to avoid hay fever.

Q: You were on stage by yourself? Did you have patter? Were you a showman?

A: I had no patter. I didn’t have any show. That evolved in Los Angeles the next year.

At The Ashgrove, the opening act there was Rene Heredia, who was 17 years old and on fire at that point. He was this kid who had come from Spain, and I guess he had some things to prove, and he just really impressed me. I didn’t see him again for 15 or 20 years when I moved to Denver.

I went back to New York and I lived with Karen for three or four months, and in the course of that time I met John Phillips, who had been part of a band called The Smoothies — I played on a session with them — and it was clear that their label Decca wasn’t interested in them as a folkie-pop thing like The Kingston Trio.

John knew a guy named Scott Mackenzie, who was the lead singer in The Smoothies, and the three of us would form a trio. Because I was living with Karen, I suggested we try and put Karen in the group. John was a lot more worldly than I was, and he knew very well that my relationship with Karen wasn’t going to go very far.

We had two of the very worst rehearsals I’ve ever had in my life, which consisted of Karen arguing about vocal parts with John. John was a great vocal arranger, and his idea of fun was he’d get five people in a room and give each of them apart, and they might sing anything — it might be “The Teddybear’s Picnic,” it might be “Tom Dooley,” whatever, he was really into vocal music.

…I don’t know that I ever became a great showman, but I learned how to tell stories on stage, and that was a revelation to me.

Around this time I met a woman named Barbara Dane, who was a white blues singer and sang with Dixieland bands. She had a tour of the Northwest and she offered me this tour, so I called John Phillips and said, “Are you serious about this band because I just got a chance to play Portland and Seattle.”

He started to laugh and he said he had just turned down a trip to the beach in Ibiza so that he could start a new group.

I said, “Okay John, I’ll be there.”

Q: Before we get too far, give me a couple of sentences more on Karen Dalton and the different sides of her talent and personality.

A: When I met Karen, she used to sing a lot of mountain music, some blues, in fact, I think she was doing “Blues on the Ceiling” by Fred Neil even then, and she sang loud, and not in a lethargic way but in an energetic way.

She was never a really good performer because she had a lot of unresolved hostility. The audiences tended to bring that out in her, and it got a lot worse if she decided she wanted to be drinking.

Years later, when I heard her first records, there was this sort of behind-the-beat, lethargic, pseudo-Billie Holiday type of phrasing, which has turned into, in a small way, a vogue among feminist and music historians who’ve typed her as a white Billie Holiday, which to me was a joke.

I thought, “That’s not what she sounds like.” She was particularly noted for her wild mountain harmonies, not this [he affects a slowed-down, overwrought vocal] “Blues on the Ceiling” type thing, which to me just sounds like a junkie…which she was.

It’s what she’s famous for. This French record producer and another guy in Nashville who are enamored with Karen have issued at least five CDs of Karen, and only one of them has what I’m talking about, which was recorded at Joe Lupe’s place, The Attic, in Boulder.

It has a little bit of that mountain music — open your mouth wide and just let it out — kind of singing.

Q: Did you think she was a genuine talent or…

A: I think she has a talent for doing that. I think she was not a good jazz singer. This need to create Billie Holidays among whiteys is crazy, and it also happened with Judy Roderick.

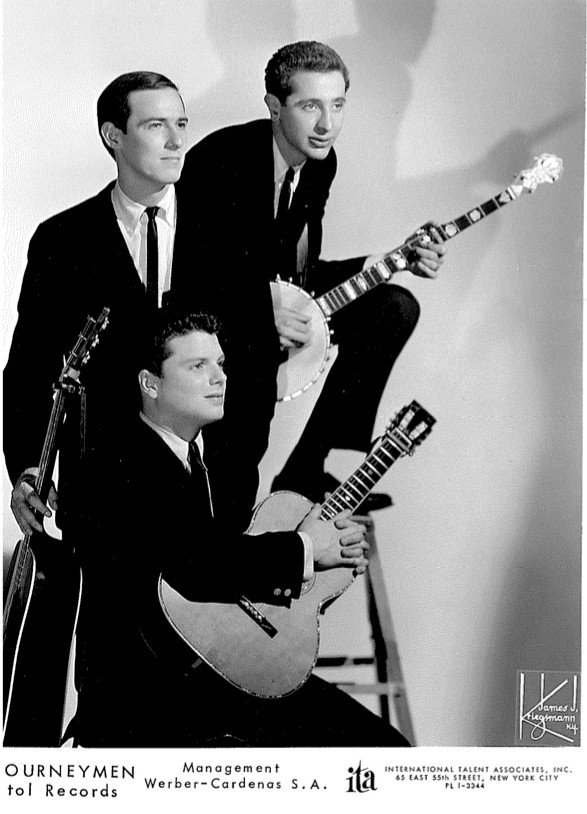

So, now I’m in New York, and we (now called The Journeymen) rehearse for six

weeks, we get a deal with International Talent, which is booking The Brothers Four, Kingston Trio, The Limeliters and later Bob Dylan, and through them, we met these managers in San Francisco.

MGM was willing to see us — they wanted to sign us, they didn’t think we had any hits. Ultimately, we had this scene where we picked up our manager, we went to MGM.

He wanted us to be guaranteed two albums a year and a five-thousand-dollar-a-year promotional budget, and one of the MGM producers looked at me and said, “You’ll never get a deal like that in the record business, and ten minutes later we were signing at Capitol Records and got that exact deal.”

That’s when I became interested in the music business, which really didn’t surface ‘til some years later when I started teaching. I filed that in the back of my mind that this business is not what people say that it is.

Somebody can say no and what they really mean is: I’d rather not.

So, we got the deal with Capitol and we toured for three and a half years. We never played in Colorado, but I would come here periodically because my friend Harry Tuft had moved here and opened The Denver Folklore Center in ’62.

At one point Scott Mckenzie, our lead singer, got nodes in his throat and we were out of work for six weeks. I just came to Colorado and Harry and I did a week at Crested Butte.

So I went from the three of us making $1,500 a night to playing in Crested Butte to Harry and I each got a room and a hundred dollars, and I went from playing for two or three thousand people to twenty to thirty people. Scott rehabbed, we got back together and our price went up to $1,750 a night.

Q: And the biggest record sold?

A: Maybe 15,000. We never got any royalties from Capitol at that point. We never recouped the original advance. Later, Bonnie Raitt got Capitol to tear up all its contracts before 1970, and so Capitol reissued all of our stuff in its Legacy Series, all three of our albums and some of our singles on the CDs.

I probably ended up making $5,000 from these; in fact, I got a check last month for $60 because it still gets streamed.

Scott and I decided to leave at the end of ’64, and I go back to New York — playing on sessions, writing songs and then producing records. I did some sessions with Gram Parsons.

Gram Parsons was a fanatical Journeymen fan. He and his band used to follow us around. Gram recorded a couple of my songs.

I also did a solo album for Capitol three or four months before we broke up because they were looking for a “Dylan,” and I was the only one that, even mildly in their mind, could do a Dylan thing.

I thought it ridiculous because I really was not doing protest songs and at that point, that’s all that Dylan was doing. I had written one song called “Lullaby for Medgar Evers” that later Judy Collins recorded.

So I did that on the album and four others that I wrote, and Gram recorded the one about mining called “They Still Go Down.”

In ’68 and ’69 I worked as a producer, and there’s a big Colorado connection there because I had maintained my friendship with Harry Tuft and he sent me a tape of a band called Frummox, and I ended up producing them in New York.

Those were really, really kinda cool sessions. I had hired Eric Weissberg to play some fiddle and mandolin and pedal steel, and at the end of the sessions he came to me, and he said, “Every five years I do something I like and this was it for the next few years.”

They were really good. Everything kind of clicked. Harry also sent me a tape of a band called Zephyr. I didn’t produce them but I did go to see them, and I took the tape to my boss and we all thought I wasn’t the guy to do it.

Q: Did you recognize anything in Tommy Bolin?

A: No. I thought they were a sellable white, psychedelic blues thing, and I wasn’t a huge fan of that music, but Harry and, in effect, I were partially responsible for them getting a record deal. But in ’69 the entire label group I was working for [ABC/DUNHILL] was fired.

I was still playing on sessions, and more and more of them were jingles. I was studying jazz guitar pretty seriously with Barry Galbraith, who was the studio guitarist I admired the most. He was number one and maybe Bucky Pizzarelli was number two.

I wasn’t playing the banjo very much and began to question why was I even doing this.

Pop Music to Teaching and Writing

Q: So at this point, the world of “pop stardom” exists. It is clear. The Beatles and Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan exist. How did you avoid the pitfalls of that lifestyle that both John Phillips and Scott Mckenzie suffered?

A: John was in effect, my mentor. I saw him destroy himself over a period of years. When I first met him, he was drinking too much and taking uppers and it wasn’t really pleasant to be around him.

Scott didn’t have a particular vice — whatever he did, he would overdo. It seemed to me like childishness. I started growing up. I got married in ’65 and it never quite made sense to me, that whole business of having to lie to people all the time, making everybody unhappy all the time.

We stayed in touch after The Mamas and the Papas got big, and this must’ve been in ’66 or ’67 and he invited me to a concert at Forest Hills. He forgot to put me on the guest list and it was $10, so I left.

I did go to the party at the St. Regis Hotel afterward…there’s a table and on the table, there’s coke, hash, pills, and another table with vodka, gin, whatever you want.

He looks at me and says, “I’m the perfect host, what would you like?”

So I said, “How about a beer?” As I’m saying this, their road manager was stoned out of his brains on acid and walking on the ledge of the sixth-floor balcony.

I’m thinking I don’t really want to witness this. So I had a beer and quickly left. I just didn’t see the point in all this.

By the late ‘60s, I still had my hay fever and came out to Colorado to vacation with my wife. While I’m here I get a call to do a Texaco commercial. I’ve had jingles that end up paying two or three grand for an hour’s work, ‘cause you don’t know how it’s gonna be used when you’re recording it.

So I really couldn’t not do it, plus the fact is that if you turn down people very much, they stop calling you. I had told Harry, “I’m gonna come here.”

He said, “You’ll never come here, you’ll always get these calls from people, and you’ll end up doing this shit-whatever it is.”

By ’72 I was becoming unhappy enough with the music thing that it was also penetrating a lot of aspects of my work and my life. I came out here. The summer before I had seen a brochure from the University of Colorado Denver that they were starting a music business program.

David Baskerville was the guy who started all this. I went down and talked to him, and they liked the idea of someone going to school there who had actually had a lot of experience in the industry, so I came out here and enrolled at UCD.

The first thing that happened when I moved here was I started to play the banjo again, which was just bizarre. It wasn’t really a conscious choice.

Q: You immediately got into a music scene in Denver, such as it was, through Harry?

A: Through Harry.

Q: What was the music scene in Denver like then?

A: Well, The Folklore Center was the center of stuff. Walt was still sorta in and out, but his preeminence had kind of eroded and he had gotten involved with various clubs where he…somehow he got involved with an Irish pub or something.

Harry had a string of people work for him: Kim King, who was in Lothar & The Hand People; Mike Kropp, who was a banjo player and ended up in a bluegrass band in New England; Paul Hofstadter a luthier who was a renowned builder, restorer, and player of folkie instruments.

Those guys had gone by the time I got here, but Harry had a little music school and I taught there about 20 hours a week, going to school and trying to be a family person.

When I stopped teaching lessons there, I pretty much stopped teaching music, except for a very short period at Swallow Hill.

I was in a band called The Main Event that was a mediocre lounge group that played Pueblo, Casper, Cheyenne…mostly conventions.

I played electric guitar and banjo — did all the Doobie Brothers stuff, whatever was popular at the time: some country, some rock, which was basically a paycheck for me, I didn’t enjoy it.

Then I got involved in writing film scores. I wrote two feature film scores, I wrote about five documentary film scores and I did a TV show for Channel Six (Rocky Mountain PBS). Harry was sort of the executive producer on all this stuff, but I wrote all the music.

The main film was called The Edge. It was done by Roger Brown, who did Downhill Racer, and Barry Corbett, a film editor who was an Olympic skier who’d crashed into a mountain while filming and was a paraplegic, and he had a film editing facility on Lookout Mountain.

The documentaries were all done with a guy named Dick Alweiss. I did a number of things for John Deere Tractors; they’d do these little film shows where they’d introduce the new line and you’d come up from Oregon or Missouri in your car, and while we’re trying to convince you to buy a 40 grand tractor, we give you some beer, a few pretzels and show you a couple of short films.

These were three-to-five minute films and they were fun to do; from ’74 to ’80 I was doing that stuff. I was teaching at Colorado Women’s College starting in’75 while still going to school at UCD in music business.

Tom McCluskey was the guy who was the head of the department and was the music critic for The Rocky Mountain News, before Justin Mitchell.

In the meantime, I had met Wesley Westbrooks, who was a black guy who originally was from Arkadelphia, Arkansas.

When he was 10 years old, he was driving a wagon delivering milk and ice cream and the guy who owned the store; his daughter ran a retail outlet and people in the town saw Wesley, who was black, talking to her and she gave him an ice cream cone without charging him.

They came to his father’s house that night and said, “You need to get your kid outta here tonight or he’s gonna get killed.”

He moved to Denver, and he got a job working for United Airlines cleaning airplanes, and he wrote about four songs that The Staple Singers recorded, none of which he’s credited with.

The most famous one is “He Don’t Knock,” which was recorded by The Kingston Trio. He also did a song called “Hear My Song Here,” which Pentangle recorded in a really nice version.

I wrote a grant to the National Endowment for the Humanities to write a biography of him; it’s the only book I have ever written that I couldn’t sell. I got the grant and spent a year.

It was a wonderful experience. I wrote up the whole thing — this was the Reagan years and I still have the manuscript, it’s called A Good Time in Hard Times. I learned a lot of stuff but I couldn’t sell the book.

I had written a book called The Folk Music Source Book in ’76.

That book came about accidentally, where Harry knew somebody who was a writer and she had been at Knopf, which was one of the most prestigious publishing companies, and she started talking with Harry, who’d a written a catalog: The Denver Folklore Company Almanac or whatever.

Knopf said they’d be very interested in talking to this guy. So she came back and talked to him and Harry being Harry, he did nothing.

So one day I said, “Look, you’re a moron: Here’s one of the best publishers in the whole goddamned world, and they’re asking you to write this book. What can I do to help you to do this?”

He said, “Why don’t you do it? You know how to write, you know how to do this stuff.”

At that point, I hadn’t written any books, but I’d written instruction books for banjo and guitar – a lot of them. The book was reviewed everywhere. It was reviewed in Rolling Stone, The New York Times, The L.A. Times.

Basically, that’s how I got into the book-writing game. That book won the ASCAP Music Critics Award.

Q: That’s about the time I started to know who you were because you really started to get a name in Denver as an academic.

A: I had worked for 14 months at The Grammys as their educational director. That was pretty horrible. I thought I would be some kind of huge hick there, but it turned out everybody there was a huge Streisand or Neil Diamond fan and that I was like a left-wing hippie.

In the middle of that, I taught at Colorado Mountain College, which had a songwriting workshop for ten years in Breckenridge. It was great! You got a condo. I brought Steven Fromholz from Frummox in.

I was doing the musician juggling act: I was writing instruction books, I was writing books, for a couple of years I taught at Swallow Hill, I did gigs with The Main Event, and I did what gigs that I could get. I ended up playing at Winnipeg three times, which was great. And I taught at Colorado Institute of Art for a year.

I started teaching at UCD in 1990. While I was there, there was a union called the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union, and I ended up doing music for two of their conventions and a CD, and some of the music led to a play about Karen Silkwood. And I did music for a play by a professor named Larry Bograd who was then at Metro about the Ludlow Massacre. So that was all going on.

At UCD I taught music business mostly, and I created a lot of classes; my favorite was Social and Political Implications of Music. A lot of the stuff I taught about –contracts and stuff – after 12 years of it, it wasn’t that interesting to me, honestly.

Ultimately, I was head of the department for two years and the turf wars and the politics just drove me crazy. During this time, for some reason, I got good at writing grants, and I brought Peggy Seeger here with a grant, I brought Len Chandler, who was a black protest singer who was arrested like 50 times.

I brought a Native American guy, Vince Two Eagles from Montana, and there was no King Center, no performance space, so they were mostly playing in classrooms.

I got a grant and we set up a label, CAM Records. The last thing I did at UCD was a class on Advanced Record Production. I brought three kids in from Jamaica; I had taught at a Jamaican governmental trade show and then at two songwriting boot camps while I was at UCD.

So we selected three writers, they came here, the orchestra was a combination of UCD students and faculty, and the producers were students. It’s a good experience for people.

Back to Denver

In 2003 Dick moved to Oregon, where he stayed until 2012 when he returned to Denver.

Q: You were happy to come back here and…it’s different from the place it was one you first came here.

A: The congestion and traffic are troublesome. There have been a lot of generational changes that I don’t especially appreciate. There’s no point in getting upset about it because that is the world.

That’s not Denver, that’s everywhere.

There are other changes that are not Denver, as the demise of the recording medium. I’m very into albums.

When I do an album it’s not just 12 songs, there’s some relation between the songs, and I’m not really interested in having people pop off one tune in a four-part suite, when in fact, it makes no sense.

It would be like taking a Hemingway novel, and you’ve read the first quarter and you just throw it away, because “Well, I read the first quarter, what more do I need?” That’s the way kids consume music.

Q: That’s exactly where I wanted to come back to, because we talked early on about how you discovered music, that process, how there seems to be something of value in that archaeological process or the organic process that you did of buying the 78s and going to see Pete Seeger, listening to what he said. It seems that the way people gather information and art now has fundamentally changed the role of art.

A: I think it’s changed the role of art. And another thing that happened is, as a musician at the age of 22, I could work at Folk City for a week or two weeks. Where do you work in Denver for a week? Nowhere. You work one day.

There’s no money, and worse than that, there’s no development. I was at The Ashgrove for three weeks. During that time I basically learned some performance skills. If I had been there one night, what would I have learned?

Right now I’m doing a paper on the musician’s union, which I’m presenting at The Music Business Educators Conference. Go to Nathaniel Rateliff, who is a pretty big success.

In 2019, someone like the young Nate (let’s make him 22) is here now and he’s making his own records, he’s booking his gigs, he’s managing his career: What does he need the union for? So, the union has not been able to…what can they do for him? There are things they could actually do.

Suppose they bought a new building and make it into rehearsal studios and if you’re a member of the union, the rent is $20 an hour. That would save him a lot of money. But it’s not available to you if you’re not a member of the union.

For the hip-hip people, you have classes on this is what ASCAP does, this is what BMI does, this is what CSAC does. Nobody’s ever done that. The union has no contact with managers. Managers run the game now.

Managers often confiscate or own, depending on your degree of cynicism, half or all of the acts’ publishing. He’s making more money, and then he probably turns ‘round and commissions our songwriting money. Kids don’t know that.

The Fray went to UCD, two of them in the music business, but they had to sue to get out of their management contract. What if the union actually negotiated with managers? There are things they could do.

Q: So is there a bit of positive that you can see in the modern landscape to give hope?

A: There are a couple of dozen musicians around like Bill Frisell, like Ron Miles, and there’s a niche for these people who are doing something new. The challenge is to create, whether it’s radio, whether it’s streaming, whether it’s the union sponsoring some concerts of music for music’s sake, and I think the university has abrogated its role in that regard. Okay, let them teach tech and music business, but what about music? How do we make that bridge? The musicians are out there. There is good stuff around.

Q: How do you find young musicians that you like specifically, and do you have hope for this next generation? Or will it keep going at all? If there’s no skin in the game because the internet has accelerated everything so much that nobody actually has to learn anything, what is the incentive to become a great musician?

A: With the explosion of Dylan and The Beatles, we had this explosion of a generation that grew up thinking, “I could do this, I could make two-to-three million dollars a year, own two or three houses, have four cars, go through multiple wives, multiple drugs, whatever. Maybe what we’re coming down to in a way is a world where we’re going back to the musician in the loft. The people who are going to do significant work are just going to say, “I don’t buy into this, and anyway I can’t win this game. What I’m going to do is what I always wanted to do, which is to do music.”

I think the music is there. The question is, how do we create the mechanism for the music to be heard?

__

Trying to label Dick Weissman as just a musician, teacher, author, philosopher or historian is simply inadequate. He’s an incredibly rare bird in the world of music. He is an adult, someone who made his way in the music business by exploring and mastering it, then being the smartest guy in the room about nearly any facet of his chosen field. He did what he wanted at the same time he was doing what he had to do to keep home and hearth together. In a world of tarnished myths and rampant bullshit artists, Dick Weissman is a breath of fresh air.

Featured Photo Cred: northstarmedia.com