Red Rocks

The Beginnings

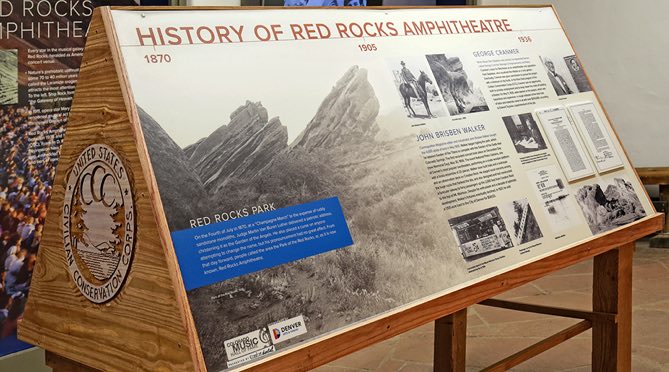

On the Fourth of July in 1870, at a “Champagne March” to the expanse of ruddy sandstone monoliths, Judge Martin Van Buren Luther delivered a patriotic address, christening it as the Garden of the Angels. He also placed a curse on anyone attempting to change the name, but his pronouncement had no great effect. From that day forward, people called the area the Park of the Red Rocks, or, as it is now known, Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

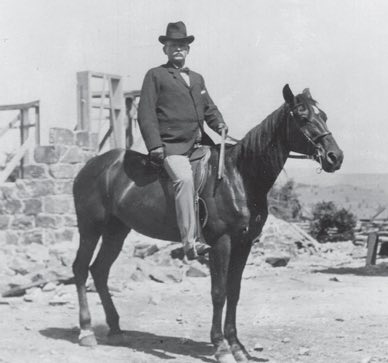

Cosmopolitan Magazine editor and industrialist John Brisben Walker bought the 4,000 acres of land in May 1905. Walker began hyping the park, which he labeled Garden of the Titans to compete with the Garden of the Gods near Colorado Springs. The first recorded concert took place on Decoration Day (now Memorial Day), May 30, 1906.

“Elusive Butterfly” The event featured Pietro Satriano, one of Denver’s most popular bandleaders, performing on a crude wooden platform with a brass ensemble of 25 pieces. Walker soon built trails and a teahouse and an observation deck on Creation Rock. He staged vocal concerts among the huge rocks that flanked the site, and also designed and had constructed a funicular railway to ferry passengers up the 2,000 feet from Creation Rock to the top of Mt. Morrison.

Despite his enthusiasm and a decade of optimistic development, Walker’s fortunes eventually declined. In 1927, he sold a 1,100-acre tract to the City of Denver for $54,133.

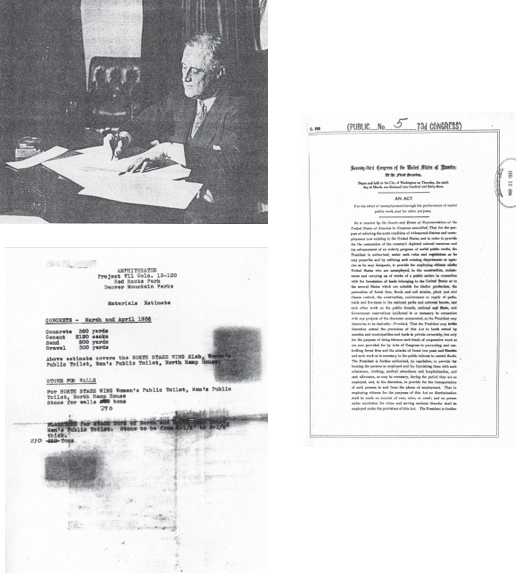

When Mayor Ben Stapleton was elected, he appointed Denver native George Cranmer Manager of Improvements and Parks. Cranmer’s vision for Red Rocks as an amphitheater met opposition from Stapleton, who visualized the hillside as a rock garden. Eventually, Cranmer was given permission to pursue the project with a minimum of city funds. In the New Deal program of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Cranmer saw an opportunity both to provide employment and to keep down the costs of building a theater. On May 11, 1936, work started on the project, which was hazardous and expensive—a rough estimate of the total cost of labor and materials came in at well over $300,000, according to Edward Teyssier, superintendent of the job.

Architect Burnham Hoyt, a young Denver architect who had helped map out New York’s Radio City Music Hall, was employed to lay out a feasible seating plan for the Park of the Red Rocks. Devoted to enhancing the unique natural setting, Hoyt designed the venue to be tucked between the massive rocks. He attempted to blend the walkways and dressing rooms into the rocks as unobtrusively as possible. An orchestra pit built of stone fronted the stage; behind it, in full view of the audience, the lights of Denver would mark the horizon.

The project went smoothly, sometimes to the accompaniment of a cappella grand opera, as Cranmer brought a steady stream of artists in the park to test and retest the acoustics. The formal dedication of the new venue took place Sunday, June 15, 1941.

Civilian Conservation Corps & Red Rocks Amphitheatre

Four years into the Great Depression, funds were scarce, and something had to be done about the army of unemployed in Denver. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s pet projects in pushing anti-Depression New Deal legislation. Congress authorized the CCC in 1933, shortly after FDR took office, and appropriated funds to create jobs all over the U.S. The plan was to recruit young men into an army of conservationists that would rescue the land, forest waters and build national, state, country and city parks and at the same time save the youths themselves. George Cranmer used his influence and persuasion to arrange help from the Works Progress Administration, to build access roads through the park. The CCC youths then undertook one of their largest projects—Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

By 1936, there were about 40 companies spread out across Colorado. On June 30, 1935, Company 1848 was transferred from Durango to Camp SP-13-C, Mt. Morrison to furnish manpower for the construction of the Amphitheatre in Red Rocks Park.

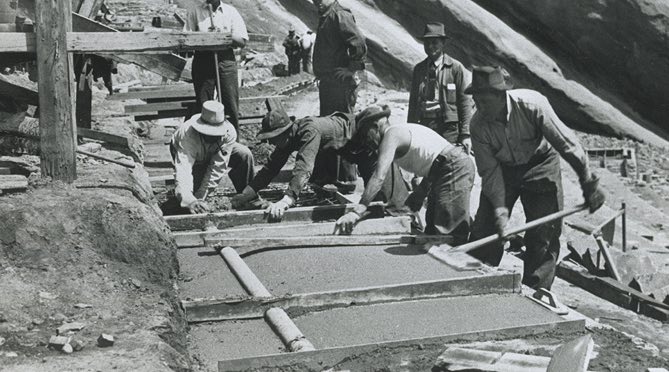

The “boys,” as enrollees were called, worked for $1 a day and room and board. They kept $5 a month and sent home the rest to help support their families. Day in and day out, the CCC veterans, stone masons and carpenters blew up the rocks, dug out the dirt, embedded the steel and then reshaped stone and concrete over it. They built the open-air venue—including a 1,260-square-foot stage, orchestra pit, dressing and control rooms, lighting system, a magnificent tiered seating area for more than 9,000 persons, and a huge parking lot—with little aid of steam shovels. Men worked mostly with picks and shovels. The difficulty of getting trucks and machinery up the winding and perilous roads made the work unavoidably slow. Muffled charges of dynamite and other blasting powder boomed through the valley daily.

Do you love and appreciate the history of music? Head over to the Colorado Music Hall of Fame, where you get to learn and enjoy the rich history of music in Colorado.